I am completing a book (under contract with University of Virginia Press) about Caribbean cultural and political responses to the U.S. occupation of Haiti. It is tentatively titled “American Imperialism’s Undead: the U.S. Occupation of Haiti and the Rise of Caribbean Anticolonialism, 1915-1950.”

I am completing a book (under contract with University of Virginia Press) about Caribbean cultural and political responses to the U.S. occupation of Haiti. It is tentatively titled “American Imperialism’s Undead: the U.S. Occupation of Haiti and the Rise of Caribbean Anticolonialism, 1915-1950.”

Caribbean studies scholars have noticed how Haiti played a key role for writers from throughout the region during the decolonization era. Plays, histories, and historical novels about Haiti enabled thinkers like C.L.R. James, Alejo Carpentier, Aime Cesaire, and Luis Pales Matos to engage with the region’s Africanness or imagine anticolonialism and liberation by looking back to the region’s first independent state. Yet as I thought more about, for example, James researching Haiti, writing the play Toussaint Louverture in 1934, and then publishing The Black Jacobins in 1938, it occurred to me that when we think of James’s context, we readily point to the Italian invasion of Ethiopia, the Russian Revolution, even the Spanish Civil War as part of the geopolitical imaginary he inhabited. But we rarely think of James, or any of these other Caribbean writers, as actually engaging with the status of Haiti in this period. Because of course, from 1915 to 1934—just as writers like James, Carpentier, Cesaire, or Palés Matos were turning their attention to Haiti—Haiti was itself occupied by U.S. marines.

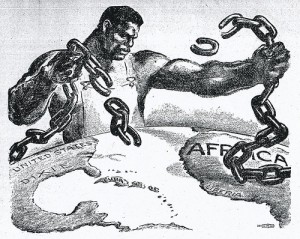

My current research, then, seeks to think through what the occupation means for how we understand Haiti’s role in the Caribbean imagination from the pivotal years of 1915 to 1950. Caribbean people like the African Blood Brotherhood and George Padmore formulated radical anticolonial projects while involved in anti-occupation activism. Analyzing the occupation–and in particular, the role of U.S. finance capitalism in engineering the intervention–forced these radicals to question political independence as the goal of anticolonial agitation and led them to see international communism as an ideology better able to critique and combat the economic exploitation at the heart of imperialism.

At the same time, creative writers like Claude McKay and Eric Walrond imagined Caribbean identity through stereotypes about voodoo circulated by U.S. culture industries during the occupation. Think of McKay’s use of a Haitian alter ego as the central Caribbean character of both Home to Harlem and Banjo, or of Walrond’s early, pre-Tropic Death stories set in Panama including one called “The Voodoo’s Revenge” that seem to respond quite directly to U.S. exotic visions of the region.

The result of placing the occupation at the center of our analysis is a new understanding of Caribbean cultural and intellectual history that engages with U.S. imperialism and culture industries in an era usually thought of in terms of European colonialism. The book provides new readings of the work of C.L.R. James, the African Blood Brotherhood, Claude McKay, Eric Walrond, Marcus and Amy Jacques Garvey, Eulalie Spence, Alejo Carpentier, and George Padmore, while also pointing the way to how other important figures like Aimé Césaire, Claudia Jones, Frantz Fanon, Amy Ashwood Garvey, H.G. De Lisser, Luis Palés Matos, George Lamming and Jean Rhys can be contextualized in terms of the occupation.